Tweet

Four Reasons to Encourage a Child’s Imagination

Four Reasons to Encourage a Child’s Imagination

It’s pretty common these days to read or hear about kids whose entire lives are scheduled. Beyond school, they have sports practices, games, clubs, music lessons…even etiquette classes. It seems that adults are competing to prepare children for a competitive world.

But what about time for kids to use their imaginations? Unfortunately, adults tend to look at unscheduled time as wasted time. Are kids really squandering time they could be using to learn something valuable? Here are four opinions that suggest otherwise.

1. Imagination improves learning The site SchoolAtoZ quotes Sir Ken Robinson, an international expert in learning, who says imagination is the "key driver of creativity and innovation" that helps children "learn with a greater appetite." SchoolAtoZ suggests reading to kids and telling them stories as a great way to fuel their imaginations.

2. Imagination helps kids cope with the unexpected In the article 10 Easy Ways to Fire Your Child’s Imagination Parenting.com cites child-development experts who say a “child with a good imagination is happier and more alert, better able to cope with life's twists and turns, and more likely to grow into a well-adjusted, secure adult.” Check out Parenting’s suggestions that include telling stories, making art and giving kids time and space to create their own thoughts, images and stories.

3. Imagination is part of normal child development In Psychology Today, Scott Barry Kaufman’s post, The Need for Pretend Play in Child Development, lists increased language usage, self-awareness, expression of positive and negative thoughts, self-regulation and capacity for creativity as benefits of imaginative play. “Research has demonstrated that parents who talk to their children regularly explaining features about nature and social issues, or who read or tell stories at bedtime seem to be most likely to foster pretend play (Shmukler 1981; Singer & Singer 2005).”

4. Imagination is what makes us human Yuval Noah Harari, a lecturer in history at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, did a fascinating TED Talk based on his research. He explored the question: How do you explain humans’ dominant position on earth? His studies led him to the conclusion that humans are the only animal that can cooperate both flexibly and in large numbers. “What enables us to cooperate in such a way? The answer is our imagination. We alone of all the animals on earth can create and believe fiction. Other animals only use their communication to describe reality. Humans create new realities. Only humans believe stories.” As examples of our fictional stories, Harari points out that human rights, legal systems, nations and monetary value are not objective realities like trees, rivers and lions. These are all stories invented by humans that allow us to cooperate on a mass scale. Harari says, “We are the only animal that can believe in things that exist purely in our imagination, such as gods, states, money, human rights, corporations and other ‘fictions,’ and we have developed a unique ability to use these stories to unify and organize groups and ensure cooperation.” It’s quite an intriguing view of imagination and well worth a listen.

Review: The Graveyard Book

Review: The Graveyard Book

(graphic novel version), volumes 1 & 2

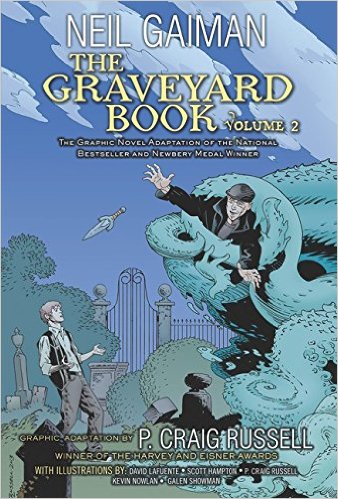

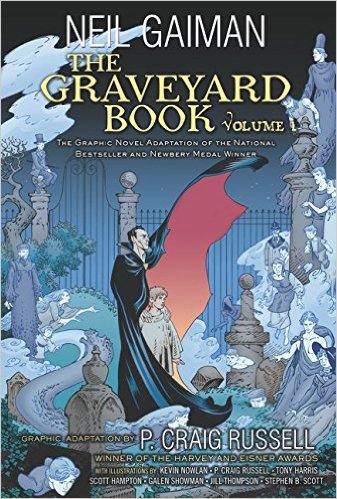

Writer Neil Gaiman is practically a household name these days. His books are bestsellers, some have been made into movies, and he's a critics' darling. His novel, The Graveyard Book, even won the prestigious Newberry Medal a few years back. Gaiman's had plenty of success as a writer of prose, but he's also equally respected as a comics writer, having created the much-loved DC series, The Sandman, back in the 1990s. This is a writer with deep roots in graphic storytelling, and so it's no surprise to see several of his most popular books adapted into the graphic novel format. It's also no surprise to see the adaptations being done by an old Gaiman collaborator from back in his Sandman days—artist P. Craig Russell.

Russell began his career at Marvel Comics in the early 1970s. His broad interests eventually took him beyond the sphere of superheroes into more personal works, like comics adaptations of classical operas (a pretty daring choice considering comics is a soundless medium). Regardless of subject matter or genre, Russell's skills as a draftsman and a storyteller make him one of the finest artists comics has ever seen. The combination of Gaiman's imagination and Russell's artistry is always worth seeking out, and a great example of what this team can do is on display in the graphic novel version of The Graveyard Book, split into volumes 1 and 2.

Try not to think of these graphic novels as the Classics Illustrated version of Gaiman's prose novel. Both version of the story of Bod Owens, the orphan raised in a graveyard by the spirits that live there, are well worth your time. The two versions are complimentary rather than redundant (trust me, I've read both). The graphic novel version is adapted by Russell, who's page layouts, rhythm and pacing are a joy to behold. Russull trades chores on the finished art with some of the best comics artists working today, including the great Kevin Nowlan, whose work is a real inspiration.

The thing I really like about these two volumes is that they buck the trend of so many graphic novels for kids these days, which seem to be draw at the level of the lowest-common-denominator: they have a cartoony, generic feel that says the artist was either a mediocre draftsman, or was trying to churn out pages as fast as possible—or possibly both. No one will accuse these books of those offenses. It's a tale wonderfully drawn, beautifully colored, and intelligently told. Gaiman's suspenseful story, engaging characters and macabre imagination will hook kids (and adults), and Russell and his artistic partners will reel them in, making these books two of the finest graphic novels for kids you can find. If you have middle-grade or older kids who you'd like to initiate into the world of sophisticated graphic storytelling, Russell's volumes of The Graveyard Book are a great way to get them started. (And do yourself a favor—read it yourself before you pass it on to them.)

You can get both books from your favorite bookseller, or you can go here for volume one and here for volume two.

Why Kids Need Visual Literacy

Why Kids Need Visual Literacy

I grew up in the era before kids’ “screen time” was an issue. As a matter of fact, “screen time” wasn’t even a concept. The only screens we watched were TV screens—no computers, video games, iPads or iPhones. But as far back as I can remember, my limited sources of visual images—yes TV, but most often comic books—made a huge impression on me.

You might say, “Well that makes sense. You’re an art guy.” I suppose that’s valid. But more often than not, the comic books I was reading back then were created by masters of visual communication. Through their work I developed what is now called visual literacy.

So what does “visual literacy” mean? Wikipedia’s definition is pretty straightforward: “Visual literacy is the ability to interpret, negotiate, and make meaning from information presented in the form of an image.”

As for why kids need it, here are some good reasons from the experts:

• Visual literacy helps us communicate better. In this interview with The National Children’s Book and Literacy Alliance, award winning author David Macauley says, “The greater our visual vocabularies, the easier it is to communicate with precision and passion, to ‘illustrate’ what we are trying to say, and to better understand what someone else is trying to say to us.”

• Images can communicate ideas and emotions in a powerful way. Edutopia interviewed the great Martin Scorsese, who emphasized the need to “…reach younger people at an earlier age to shape their minds in a critical way of looking at images and what they mean and how to interpret imagery… Images are very powerful. We have to begin to teach younger people how to use them and to interpret them.”

•Visual images saturate our 21st century lives. Kids need to be able to decode what they see. In this blog post, Todd Finley of Edutopia says teaching visual literacy skills helps kids learn to “think through, think about and think with pictures.”

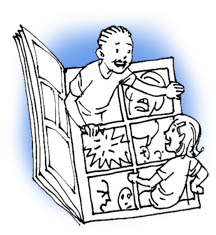

The topic of visual literacy can get pretty academic. But even asking kids a couple simple questions while you’re reading a picture book, comic book or graphic novel together can put them on the road to visual literacy. Try asking, “what do you think is happening in the picture?” and “what do you see that tells you what’s happening?”

Small conversations can open kids’ eyes to the meaning in the images around them.

When Are Kids Too Old For Read-Aloud? Never!

When Are Kids Too Old For Read-Aloud? Never!

I have a guest-blogger for this week's entry: my wife, Kim Kent! She's here to talk about a very personal aspect of how we raised

our kids...

When our kids were young, Jeff and I often wondered (as I’m sure most parents do) whether we were doing the right things for our kids. The one thing we never questioned, however, was reading aloud to them. I clearly remember reading a book to our daughter while she happily kicked her month-old legs. Obviously she had no idea what I was saying—the book, after all, was The Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen. But I was determined in my new parenting zeal to start her off as a book lover.

Turns out, experts agree with that approach. In this 2015 EdSource article here the author cites research by Dominic Massaro, a professor emeritus in psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who studies language acquisition and literacy. Massaro’s study found that “Reading aloud is the best way to help children develop word mastery and grammatical understanding, which form the basis for learning how to read.” Reach Out and Read, a nonprofit that incorporates books into pediatric care, references the findings of numerous studies to support benefits of reading aloud: It “…helps children acquire early language skills… develop positive associations with books and reading” and “…build a stronger foundation for school success.” Who can argue with those results?

Reading aloud remains important, even as kids get older. GreatKids, a site with research-based articles, videos, and worksheets to help parents support their children’s learning, interviewed Jim Trelease, educator and author of the Read-Aloud Handbook. Trelease says, “A child’s reading level doesn’t catch up to his listening level until eighth grade… A fifth grader can enjoy a more complicated plot than she can read herself… when you get to chapter books… there is really complicated, serious stuff going on that kids are ready to hear and understand, even if they can’t read at that level yet.”

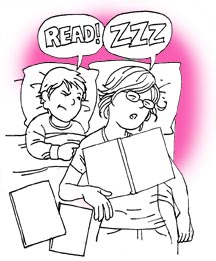

In our family, bedtime reading was the ritual. From the time our kids could sit in our laps, Jeff and I would take turns reading to each of them before bed. They pretty much thought it was their birthright that we would read to them, every single night, no matter how tired we were. I had a habit of falling asleep mid-sentence, which would prompt my son to give me an elbow to the ribs and say, “Read!” I read the first several Harry Potter books aloud to both children, sometimes in three-hour marathons when I would lose my voice, and the kids became avid readers of the series. When the last of the series, The Deathly Hallows, was published in 2007, my daughter and son—young adults at ages 19 and 17—had to have their copies at midnight on the release night, and finished them in a weekend.

Of course reading aloud isn’t the only precursor of a child’s future abilities and achievements. But our experience, although just that—a single family’s experience, certainly bears out the research. Our daughter has just completed her master’s degree in urban education at Johns Hopkins University, and our son is working on his second bachelor’s degree, this one in electrical engineering at Southern Illinois University. And I’ll tell anybody who’ll listen that reading to our kids is one the most important things we did as parents.

Yes, Comics Are Good for Kids!

Yes, Comics Are Good for Kids!

I begin this post with a disclaimer: I grew up as an avid (read that rabid) comic book fan. I’ve gone on to become an entrenched student of the form: its history, its artists and its place in American culture.

Based on that admission, you might expect me to be biased on the subject of whether comics and graphic novels have a place in a kid’s reading repertoire. And, well…you’d be right. But let me tell you some things I learned from Superman, Green Lantern, Spider-man and all the rest of the guys.

Vocabulary: As early as age eight I encountered words like “invulnerable,” “identity” and “extraterrestrial.” I had to figure out what they meant from their context.

Adult Concepts: I first read Hamlet’s soliloquy and first encountered a reference to Pangaea in issues of The Flash. (I also learned that exposure to radioactivity will give you superpowers. Turns out that’s not true.)

Oh, and of course, Visual Storytelling: I went on to make my living as a graphic designer for decades, and then returned to the medium closest to my heart—graphic storytelling for kids.

Now, you may be thinking, “Most kids aren’t going to grow up to be artists or writers.” (True) “How does graphic storytelling apply to them?” Let’s see what educators and other parents have to say about comics and graphic novels.

In a 2011 American Libraries Magazine article, Jesse Karp, school librarian and YA author from Manhattan, explores ways the modern graphic novel fits into a school curriculum. In addition to the form’s ability to attract reluctant readers, he says, “Because contemporary students have a much wider visual vocabulary than we did growing up, I contend that the format offers great opportunities to teach as well as to entertain.”

Karp cites well-known graphic novels Art Spiegelman’s MAUS and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis as often-used supplements to history and social studies curricula. He then goes on to offer specific examples of classroom lessons using sequential art: telling a story without words, depicting emotion and action, and constructing a narrative.

As ParentMap.com post Getting Graphic: Why Comics Are Good For Kids points out, “Graphic novels demonstrate larger literary themes…Protagonist, antagonist, story arc and resolution are all there, even when the title work uses no words at all, such as Owly.”

In its parents’ blog, publishing giant Scholastic includes a post, Raising Super Readers: The Benefits of Comic Books and Graphic Novels, which lists benefits to young readers. Among them are inference, memory, sequencing, understanding succinct language, reading comprehension, critical thinking—you get the picture. It also mentions benefits to kids with learning disabilities. “Children with autism can learn a lot about identifying emotions through the images in a graphic novel…children with dyslexia…often feel a sense of accomplishment when they complete a page in a comic book.”

So, where do you start to introduce kids you know to graphic storytelling? My six-year-old nephew loves Owly by Andy Runton. The Bone series by Jeff Smith is great for middle-school kids. And if you want to jump in with both feet, GoodOkBad.com has an extensive list of Great Graphic Novels for Kids separated into Pre-K, Lower Elementary, Upper Elementary and Junior High ages. Take a look, share with your kids, and email me your thoughts.

Why Picture Books Are Important

Why Picture Books Are Important

About five years ago The New York Times ran an article entitled Picture Books No Longer a Staple for Children; the article sent a seismic shock through the children’s book business. Citing lagging picture book sales and declining new releases, the author attributed the decline in part to the economic recession, then at its height.

More controversially, the article traced picture books’ downward trend to a shift in parents’ attitudes. “Parents have begun pressing their kindergartners and first graders to leave the picture book behind and move on to more text-heavy chapter books,” as a response to the increased importance of standardized testing. While the article does go on to quote children’s publishers and booksellers on the virtues of picture books, that message seems to have been overshadowed.

Regardless of dire predictions, the picture book has its advocates, present company included. As blogger and former Kindergarten teacher, Susan Stephenson, said, “As for pushing kids onto chapter books, why?... What are we afraid of, when we stop kids reading picture books?... A picture book is like a window to the world for kids. It introduces them to our literary heritage, to the pleasure of story, to fascinating facts, to visual and textual delights created by both author and illustrator.”

On PictureBookMonth.com authors and illustrators posted essays on Why Picture Books Are Important for each day in November. Sophie Blackall, illustrator of more than 30 books for children, pointed out that, “Illustration is one of the oldest and most enduring forms of communication…We have photography and film now to document reality, but drawing is magic.” Number six on New York Times Bestselling Author, Aaron Reynolds’ list of eight reasons picture books are important is, “A picture book has the uncanny ability to transport and inspire both kids AND adults.”

Along with many parents and teachers, those of us who create children’s books witness firsthand the magic of picture books. Not only do they transport and inspire, they engage young kids, helping them learn about their world and about how people think and feel. And the words and images stay with them for a lifetime.

So in this age of standardized testing and pressured parents, let’s relax a little and let our kids follow their instincts. Picture books should always hold a place of honor on the shelf.

So, why Robots And Quicksand?

So, why Robots And Quicksand?

Answer #1: Everyone loves a good illustrated story. The combination of illustrations and words immediately draws (pun intended) a reader into the story. And, it’s an especially powerful fusion for kids. How many lifelong readers and dreamers have been created by early exposure to comics and picture books? More than we can count.

Illustrations and words together create a one-two punch to the imagination that’s unique. Yes, prose books, movies, TV, and even video games can all feed the imagination. But stories told with sequential art have an almost magical ability to engage and transport a reader.

RobotsAndQuicksand.com is dedicated to the limitless power of the illustrated story. Adults are welcome here, but this site exists to help kids experience the exciting, informative, inspiring, entertaining—and just fun—art form they instinctively love.

Which leads to Answer #2: As I see it, robots and rocket packs, superheroes and spaceships, dinosaurs, monsters, bottomless pits, cowboys, castles and yes, quicksand are essential ingredients of childhood. Fun and adventurous stories fuel kids’ sense of wonder about the world. Experiencing an imaginative tale can even open kids’ eyes to life’s possibilities—prospects bigger than those in their everyday lives.

It’s my firm belief that any kid who’s played “hot lava”—leaping across living room couch cushions to escape marauding monsters—has a head start in life. Those kids stand a far better chance of finding their way over life’s real obstacles.

I hope you—but more importantly, your favorite kids—join me in this adventure in imaginative visual storytelling.